J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 17(2):109-120.

doi: 10.34172/jcvtr.025.33347

Original Article

An integrated bioinformatics approach for identification of key modulators and biomarkers involved in atrial fibrillation

Summan Thahiem Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1

Ayesha Ishtiaq Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1

Faisal Iftekhar Formal analysis, Methodology, 2

Muhammad Ishtiaq Jan Formal analysis, Methodology, 3

Iram Murtaza Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1, *

Author information:

1Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Biological Sciences, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan

2Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Lady Reading Hospital Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan

3Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Chemical & Pharmaceutical Sciences, Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat, Pakistan

Abstract

Introduction:

Atrial fibrillation (AFib) is a sustained form of cardiac arrythmia that occurs due to sympathetic overdrive, neurohumoral and electrophysiological changes. Sympatho-renal modulatory approach via miRNA-based therapeutics is likely to be an important treatment option for AFib. The study was aimed to unravel the common miRNAs as therapeutic targets involved in sympatho- renovascular axis to combat AFib.

Methods:

We employed the bioinformatics approach to discover differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from microarray gene expression datasets GSE41177 and GSE79768 of AFib patients. Concomitantly, genes associated with sympathetic cardio-renal axis, from Genetic Testing Registry (GTR) of National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) were also analyzed. Overlapping miRNAs that target the maximum number of genes across all three pathological conditions perpetuating AFib were shortlisted. To confirm the reliability of the identified miRNAs, differential expression analysis was performed on miRNA expression profiles GSE190898, GSE68475, GSE70887 and GSE28954 derived from AFib patient samples.

Results:

ShinyGO analysis revealed enrichment in beta-adrenergic signaling, calcium signaling, as well as G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling involved in post synaptic membrane potential. The intersection of top 10 modules in miRNA-mRNA network revealed hub miRNAs having highest node degree, maximum neighborhood component (MNC), and maximal clique centrality (MCC) scores. Differential expression analysis revealed hub miRNAs identified through integrated approach were found to be significantly dysregulated in AFib patients.

Conclusion:

This integrated approach identified 6 hub miRNAs, 4 reported (miR-101-3p, miR-23-3p, miR-27-3p, miR-25-3p) and 2 novel (miR-32-5p, miR-92-3p) miRNAs that might act as putative biomarkers for AFib.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation (AFib), Bioinformatic approaches, Gene regulatory network, miRNAs, Protein-protein interaction, Sympathetic cardio-renal axis

Copyright and License Information

© 2025 The Author(s).

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the university research fund (URF) of Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Higher Education Commission (HEC) Pakistan, and Pakistan Science Foundation (PSF).

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AFib) is one of the most common forms of arrhythmia, characterized by an irregular and often rapid heartbeat. According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) report, the estimated prevalence of AFib has reached 46.3 million.1 Its prevalence is expected to increase twice or more in the next 40 years.2 AFib is associated with a twofold increase in premature mortality due to adverse cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events.3 The etiology of AFib is multifactorial, characterized by wide range of comorbidities ranging from sympathetic overdrive to neurohumoral and hemodynamic pathophysiological mechanisms.4

Sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activation has been well-known as a fundamental determining factor in AFib pathophysiology and has a significant influence on the structural integrity and electrical conductivity of both kidney and heart.5 Aberrant SNS activation can induce heterogeneous changes such as excess release of catecholamines in the circulation, hyperactivation of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), and spontaneous calcium release, enhanced beta-adrenoceptor activity thus elevating arterial hypertension and deteriorating kidney function.6,7 These actions contribute to long-term elevated arterial pressure, electro-structural remodeling characterized by conduction abnormalities and increased automaticity.8 AFib and renovascular hypertension (RVH) frequently coexist and have a close bidirectional relationship. The incidence of AFib has been widely associated with concomitant destruction of kidney physiology.9 The onset of AFib in patients with renal hypertension may reflect mechanical stress in the atrium.10 There is increasing recognition of the crucial role of the renin angiotensin aldosterone cascade in the etiology of cardio-renal hypertension, culminating AFib.11

The role of epigenetic modifications in the pathogenesis of AFib has been documented in a variety of studies, among which miRNAs have acquired significant importance in modulating cardiovascular function.12,13 The accurate diagnosis of disease-vulnerable individuals is of paramount importance. For that the identification of miRNAs and their association with disease phenotype for both prognostic and diagnostic purposes is currently under the limelight of research.

miRNAs are single-stranded RNAs that are non-coding and nearly 22 nucleotides in length. They function as “fine tuners” of gene expression and regulation. Due to their phylogenetic species conservation, highly consistent and stable expression profile, and simplicity of detection, they are regarded as best reporters of disease phenotypes. In this context, computational approaches have been an invaluable tool for miRNA expression profiling, which may aid in the early detection of chronic diseases. 14,15

Interplay of miRNAs in autonomic cross talk between kidney and heart is the best choice for exploring the pathogenesis of AFib. To the best of our knowledge, no systematic research-based study has been performed to identify highly associated genes and miRNAs of AFib using an integrated multi-step bioinformatics analytic pipeline. Sympatho-renal modulatory approach via miRNA-based therapeutics is likely to be an important treatment option for AFib. Prior studies were limited to identification hub genes targeting AFib alone by analyzing different datasets,16-19 however, no previous study has employed combinational approach by targeting genes underlying the pathological sympathetic cardio-renal axis that helps in identification of highly potent miRNAs. These miRNAs not only regulate genes involved in AFib but also influence genes that contribute to AFib development risk.

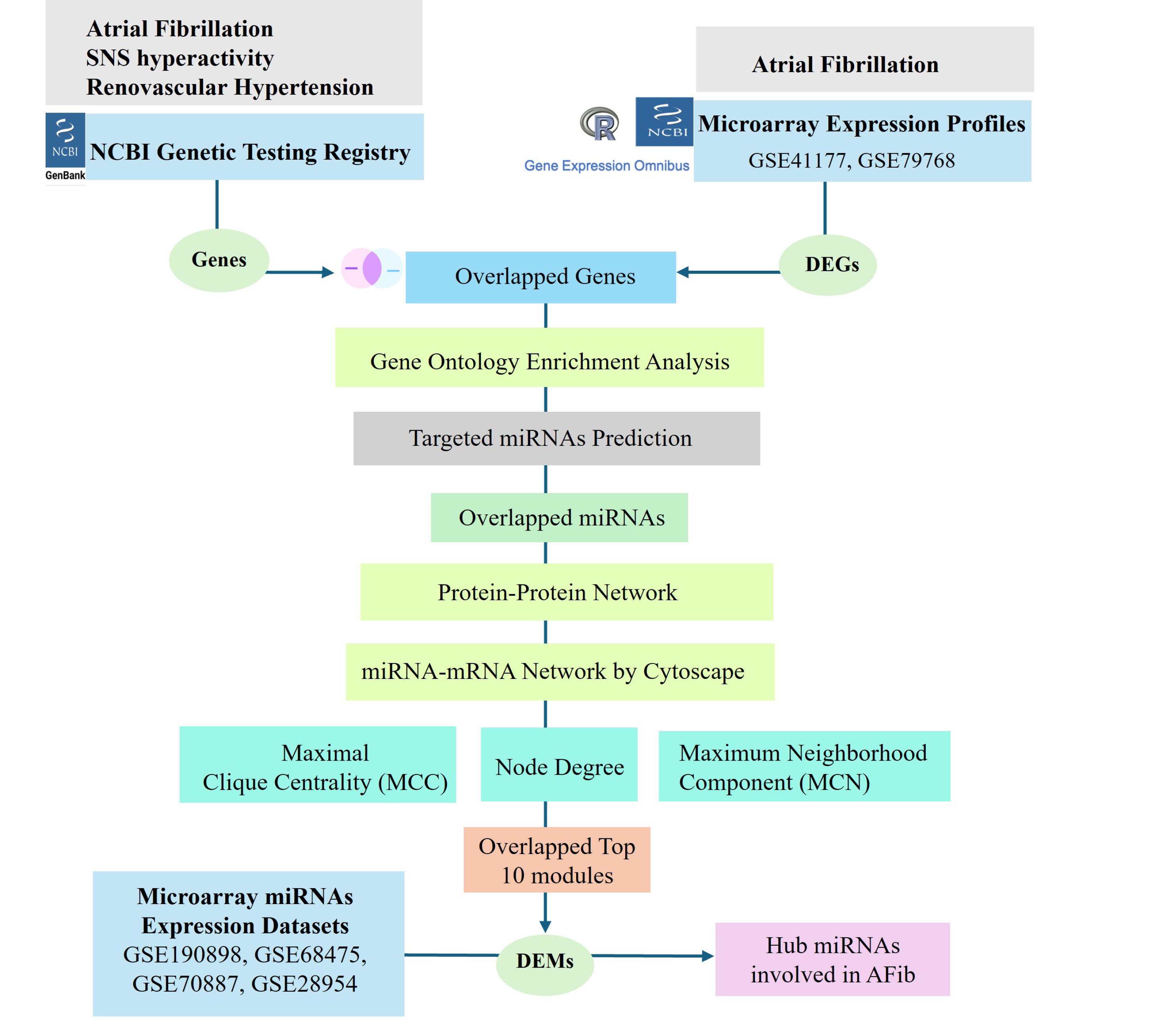

The complex interplay of heart failure and chronic kidney disease in atrial fibrillation creates a mutually reinforcing cycle that escalate disease development. 20-22 Therefore, the aim of study was to identify potential hub miRNAs by integrating previously published microarray datasets of both genes and miRNAs of AFib patients. The workflow of hub genes and miRNA screening curation pipeline from data acquisition, meta-analysis, identification of differentially expressed entities, to downstream network analysis is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The workflow of integrated analysis used in current study

.

The workflow of integrated analysis used in current study

Materials and Method

Acquisition of disease-associated genes

In this study, we analyzed the critical pathophysiological factors contributing to atrial fibrillation, especially focusing on brain-kidney-heart axis spanning from sympathetic nervous system neurohormones to renal hypertension. Thus, with the help of bioinformatics repositories NCBI GTR and Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), we selected highly specific disease linked genes that have been investigated clinically for that specific pathological condition.23

Selection of microarray dataset for comprehensive screening of genes (the discovery cohort)

Microarray expression profiles related to AFib were screened and curated from GEO repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).24 We omitted studies involving drug treatments or any other interventions, cell lines, transfected or transgenic tissues. Microarray datasets passing these stringent criteria were selected. For discovery cohort, datasets GSE41177 and GSE79768 of atrial fibrillation patients were retrieved (Table 1). After normalization and annotation of series matrix files, expression data were then analyzed through Affy package and Limma Package in R software. The Limma package specifies functions such as lmFit, eBayes, and topTable for linear modeling along with statistical testing.

Table 1.

Summary of gene expression datasets of AFib patients

|

Geo Accession ID

|

Title

|

Platform

|

Sample Size

|

| GSE41177 |

Region-specific gene expression profiles in left atria of patients with valvular atrial fibrillation |

Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array |

38 |

| GSE79768 |

Atrial fibrillation is associated with altered left-to-right atria gene expression ratio: implications for arrhythmogenesis and thrombogenesis |

GPL570[HG-U133_Plus_2] Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array |

26 |

Data processing, screening and identification of differentially expressed genes

The raw data of microarray expression profile of patients and control were preprocessed (background correction, annotation, gene symbol transformation, and normalization) to reduce confounding effects. The probes with no annotation information were deleted. Then, Bioconductor package limma was used to identify the differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Screening parameter for identification of DEGs was based on adjusted P value < 0.05, |log2 fold change| > 1 and -log10 (P value) > 1.3. Additionally, a volcano plot was generated to visualize significant upregulated and downregulated entities.

Screening and visualization of hub genes

Top ranked hub genes were deployed that were common in GTR and DEGs from microarray datasets. For data visualization, we used AI based Tableau software (https://www.tableau.com/). Overlapping entities among DEGs and Genes list obtained from NCBI GTR and OMIM were visualized using Venn diagram, utilizing the online tool InteractiVenn (https://www.interactivenn.net).25

Gene set functional enrichment analysis

The gene enrichment analysis was executed for genes associated with Sympathetic Cardio-Renal Axis, to identify statistically significant signaling pathways using ShinyGO 0.80 (http://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go/). A screening threshold of false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and P< 0.01 was applied for statistical significance of data.26

miRNAs target prediction

Hub genes were than integrated for miRNA target prediction using open-source platforms; TargetScan database (http://www.targetscan.org), and miRbase (http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw) for studying the miRNA-mRNA interaction.27,28,29 The selection criteria for miRNA was based on thermodynamic stability, evolutionary conservation, seed matching, and site accessibility to improve the target prediction fidelity. Only 8-mer, (human, rat, and mouse) species conserved miRNAs were selected for each gene.

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network construction

The Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING) database Version 12.0 (https://string-db.org/)30 was used to predict and track PPI interactions. The analysis of interactions between different proteins provides new insight to study the pathophysiological mechanisms of AFib. Using DisGeNET algorithm of Metascape (https://metascape.org) 31 genes were further examined for functional enrichment analysis.

miRNA-mRNA network construction and hub modules identification

Cytoscape (v3.10.1) Plugin CytoHubba 32 was employed to construct miRNA-mRNA network to identify densely connected entities based on 3 topologies; node degree, maximal clique centrality (MCC), and maximum neighborhood component (MNC). Entities overlapping across these topologies were selected as hub miRNAs and hub genes.

Selection of miRNA microarray datasets for validation of hub miRNAs (the validation cohort)

For validation cohort, the miRNA profiling datasets GSE190898, GSE68475, GSE70887 and GSE28954 of atrial fibrillation patients were retrieved (Table 2). After normalization and annotation of series matrix files, expression data were then analyzed through affy package and Limma Package in R software.

Table 2.

Summary of miRNA expression datasets used in this study

|

Accession ID

|

Tittle

|

Platform

|

Samples

|

| GSE190898 |

Atrial Fibrillation Patient's Urine miRNA Microarray |

GPL21572 [miRNA-4] Affymetrix Multispecies miRNA-4 Array |

8 |

| GSE68475 |

Characterizing the global changes in miRNA expression in human atrial appendages with persistent atrial fibrillation. |

GPL15018 Agilent-031181 Unrestricted_Human_miRNA_V16.0_Microarray 030840 (Feature Number version) |

21 |

| GSE70887 |

Microarray analysis of miRNAs in atrial tissue from chronic AF patients |

GPL19546 Agilent-021827 Human miRNA Microarray [miRBase release 17.0 miRNA ID version] |

8 |

| GSE28954 |

Valvular heart disease and atrial fibrillation regulate microRNA expression profiles in left and right atria differently |

GPL10850 Agilent-021827 Human miRNA Microarray (V3) (miRBase release 12.0 miRNA ID version) |

34 |

Results

Screening and identification of common genes among genes of cardio-renal axis and AFib discovery dataset

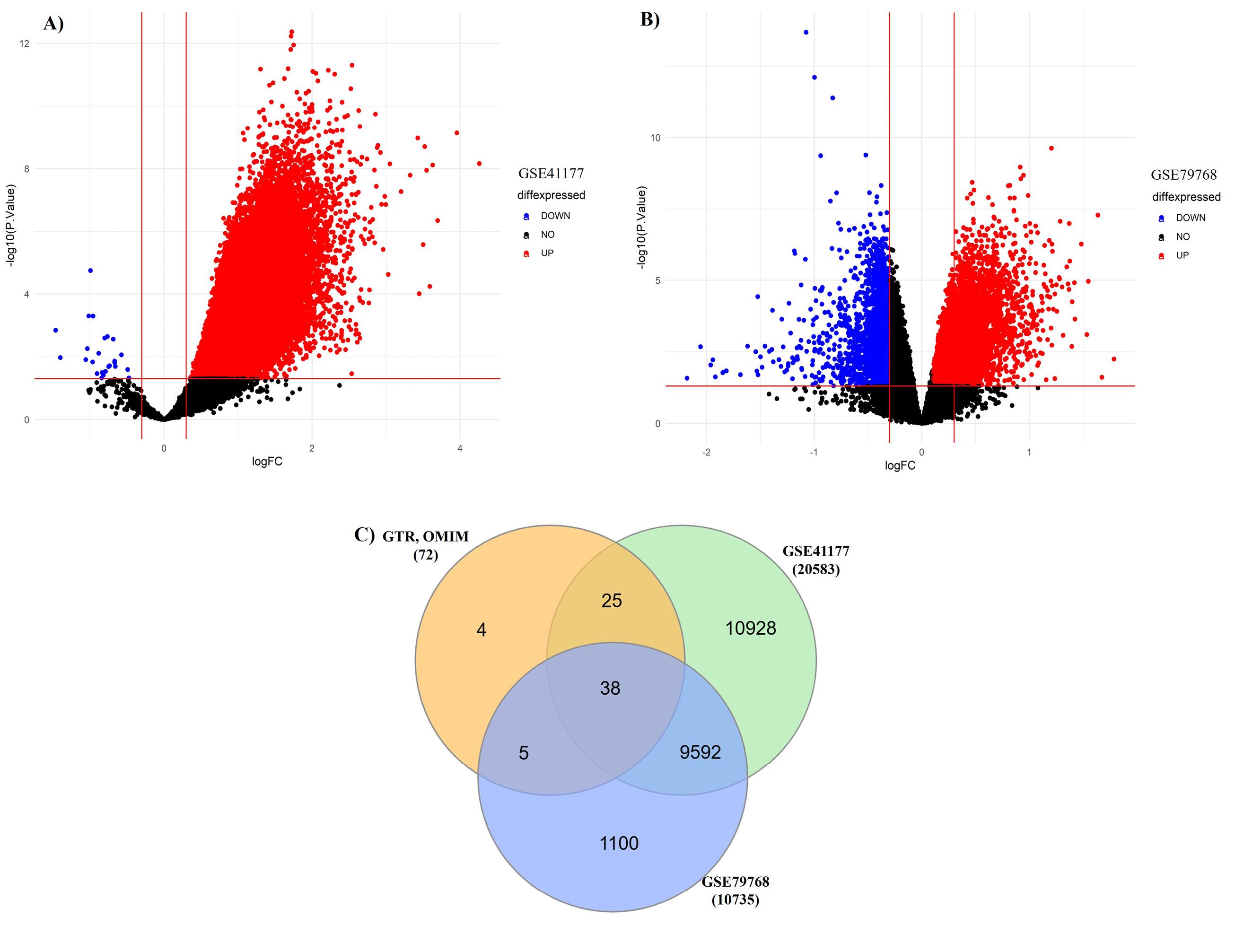

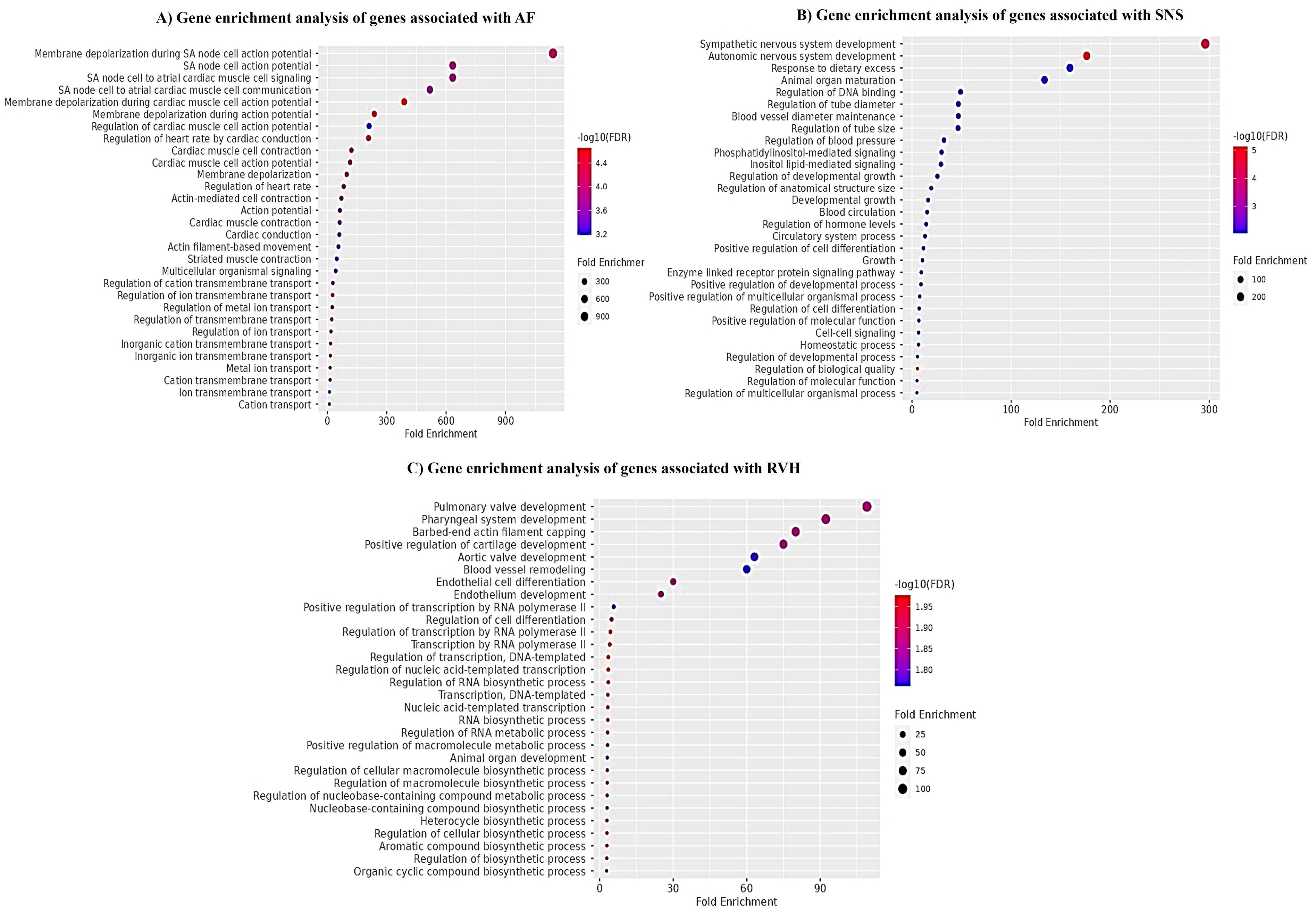

We selected disease specific genes from bioinformatics repositories e.g., NCBI GTR and OMIM as given in Table S1. Moreover, microarray gene expression profiles GSE41177 and GSE79768 of AFib patients and controls were also analyzed. The DEGs are represented in volcano plots according to the logFC and -log(P-value) values as shown in (Figure 2A & B) (Table S2 & S3). We compared gene lists associated with AFib derived from bioinformatics repositories and DEGs from microarray gene expression datasets. 38 overlapping genes were found to be involved in Sympathetic Cardio-Renal Axis and AFib. The overlapping genes are represented in Venn diagram (Figure 2C). For in-depth analysis of gene sets, enrichment analysis was performed separately on all three genes sets associated with AFib, SNS activity and RVH as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Volcano plots of DEGs; illustrating the distribution of differentially expressed genes according to the logFC and -log(p-value) values. (A) GSE41177 (B) GSE79768 (C) Venn diagram of overlapping DEGs

.

Volcano plots of DEGs; illustrating the distribution of differentially expressed genes according to the logFC and -log(p-value) values. (A) GSE41177 (B) GSE79768 (C) Venn diagram of overlapping DEGs

Figure 3.

Gene enrichment analysis (A) AFib associated genes. Many of these genes are known to underpin molecular responses such as membrane depolarization, sinoatrial action potential generation, muscles contraction, regulation of ions transmission and regulation of heart rate. (B) SNS hyperactivity associated genes. Enriched terms include sympathetic nervous system development, autonomic nervous system activity, circulatory system processes, cell-cell signaling, homeostatic signaling. (C) RVH associated genes. Genes showed enrichment in processes including blood vessels remodeling, pulmonary and aortic valves development and pharyngeal system development

.

Gene enrichment analysis (A) AFib associated genes. Many of these genes are known to underpin molecular responses such as membrane depolarization, sinoatrial action potential generation, muscles contraction, regulation of ions transmission and regulation of heart rate. (B) SNS hyperactivity associated genes. Enriched terms include sympathetic nervous system development, autonomic nervous system activity, circulatory system processes, cell-cell signaling, homeostatic signaling. (C) RVH associated genes. Genes showed enrichment in processes including blood vessels remodeling, pulmonary and aortic valves development and pharyngeal system development

miRNA profiling of overlapped genes associated with Sympathetic Cardio-Renal Axis

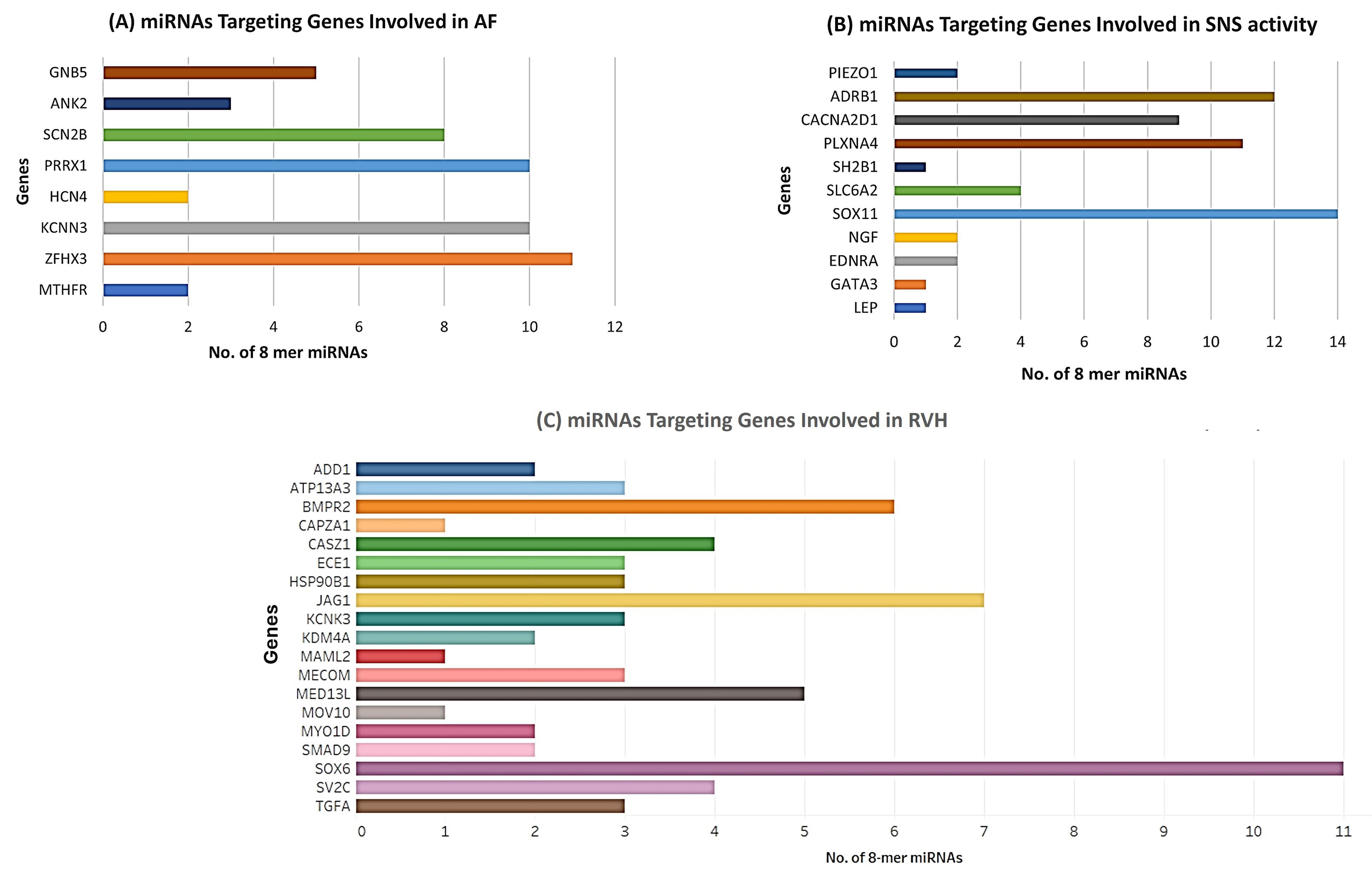

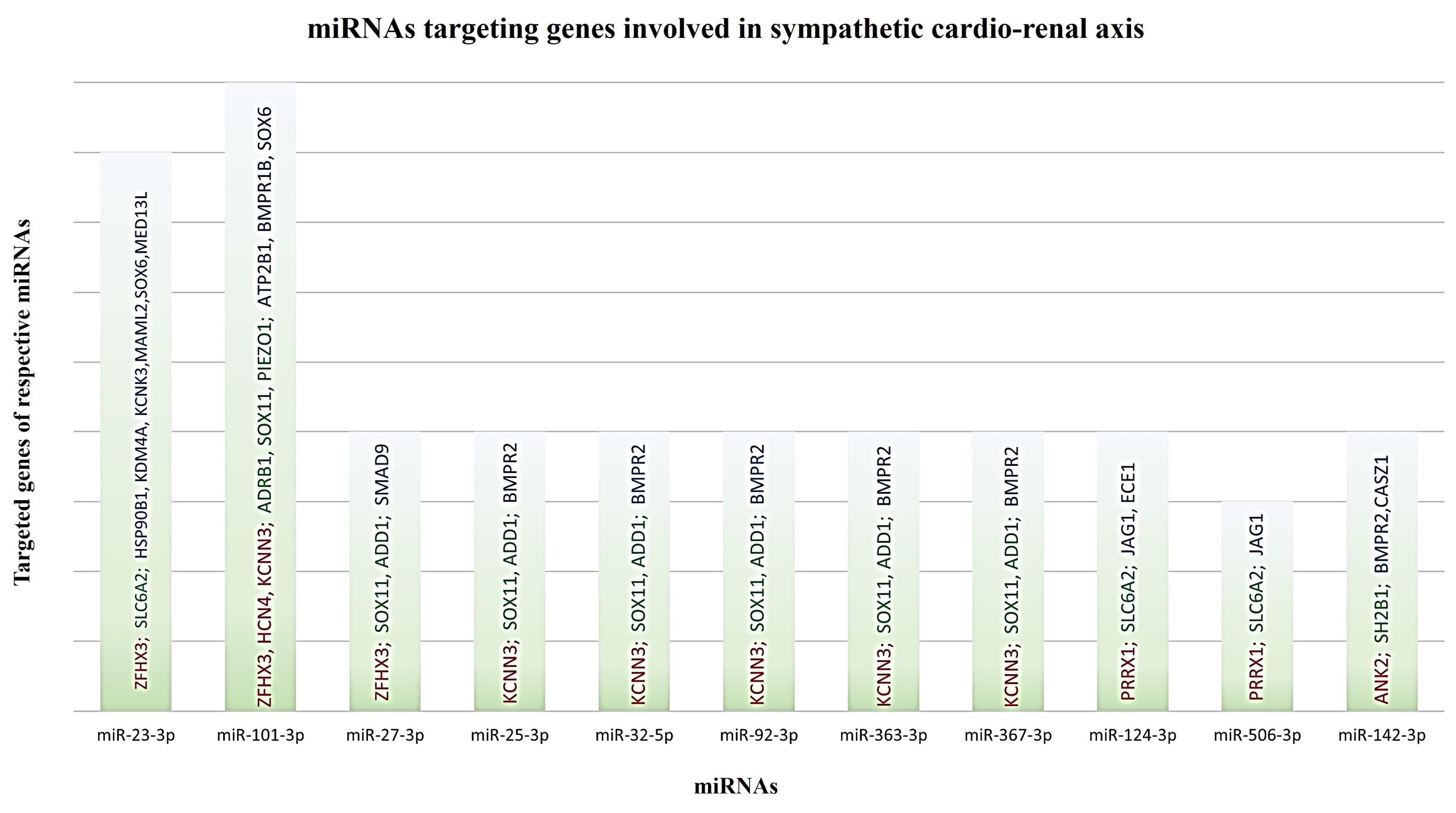

Only species conserved miRNAs having 8-mer binding seed region in the 3’ UTR of genes involved in the progression of AFib, SNS activity and RVH have been shortlisted for downstream analysis. The data are given in Table S4. Graphical representation of these genes with their respective 8-mer miRNAs are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of miRNAs associated with Sympathetic Cardio-Renal Axis (A) miRNAs targeting genes associated with AFib. (B) miRNAs targeting genes associated with SNS activity. (C) miRNAs targeting genes associated with RVH. X axis depicts the number of miRNAs whereas, Y axis shows the list of respective genes having 8-mer binding sites

.

Graphical representation of miRNAs associated with Sympathetic Cardio-Renal Axis (A) miRNAs targeting genes associated with AFib. (B) miRNAs targeting genes associated with SNS activity. (C) miRNAs targeting genes associated with RVH. X axis depicts the number of miRNAs whereas, Y axis shows the list of respective genes having 8-mer binding sites

Commonly expressed miRNAs and targeted genes involved in Sympathetic Cardio-Renal Axis

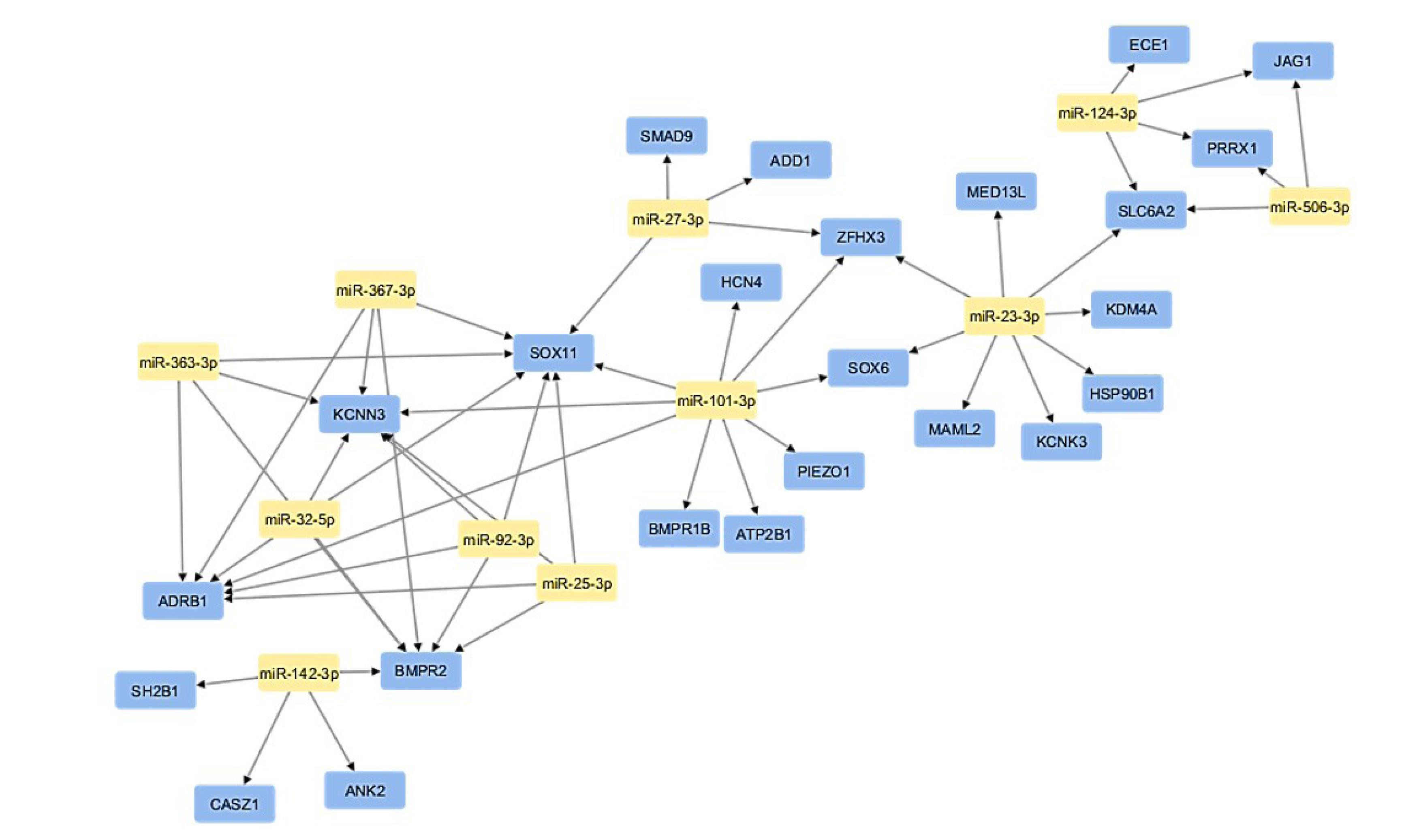

RVH and AFib co-exist frequently, and share common putative mechanisms, suggesting that common pathophysiological processes may drive both pathologies. 33 Hence manipulating the expression of genes involved in both pathologies can ameliorate the disease phenotype at earliest. Subsequently, for this purpose, we shortlist hub miRNAs common in all pathologies that target more than one gene. The key finding of our data confirms that 11 miRNAs (miR-23-3p, miR-101-3p, miR-27-3p, miR-25-3p, miR-32-5p, miR-92-3p, miR-363-3p, miR-367-3p, miR-124-3p, miR-506-3p, miR-142-3p) are targeting common genes involved in the development and progression of cardiac arrythmia and AFib as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of common miRNAs involved in all three pathologies A single miRNA can target more than one gene and is involved in more than one pathophysiological mechanism. The graph shows 11 miRNAs (miR-23-3p, miR-101-3p, miR-27-3p, miR-25-3p, miR-32-5p, miR-92-3p, miR-363-3p, miR-367-3p, miR-124-3p, miR-506-3p, miR-142-3p) that can target common genes involved in sympatho-excitation in AFib pathophysiology. Red color represents AFib linked genes; green color represents genes regulating SNS activity whereas blue depicts genes involved in RVH respectively

.

Graphical representation of common miRNAs involved in all three pathologies A single miRNA can target more than one gene and is involved in more than one pathophysiological mechanism. The graph shows 11 miRNAs (miR-23-3p, miR-101-3p, miR-27-3p, miR-25-3p, miR-32-5p, miR-92-3p, miR-363-3p, miR-367-3p, miR-124-3p, miR-506-3p, miR-142-3p) that can target common genes involved in sympatho-excitation in AFib pathophysiology. Red color represents AFib linked genes; green color represents genes regulating SNS activity whereas blue depicts genes involved in RVH respectively

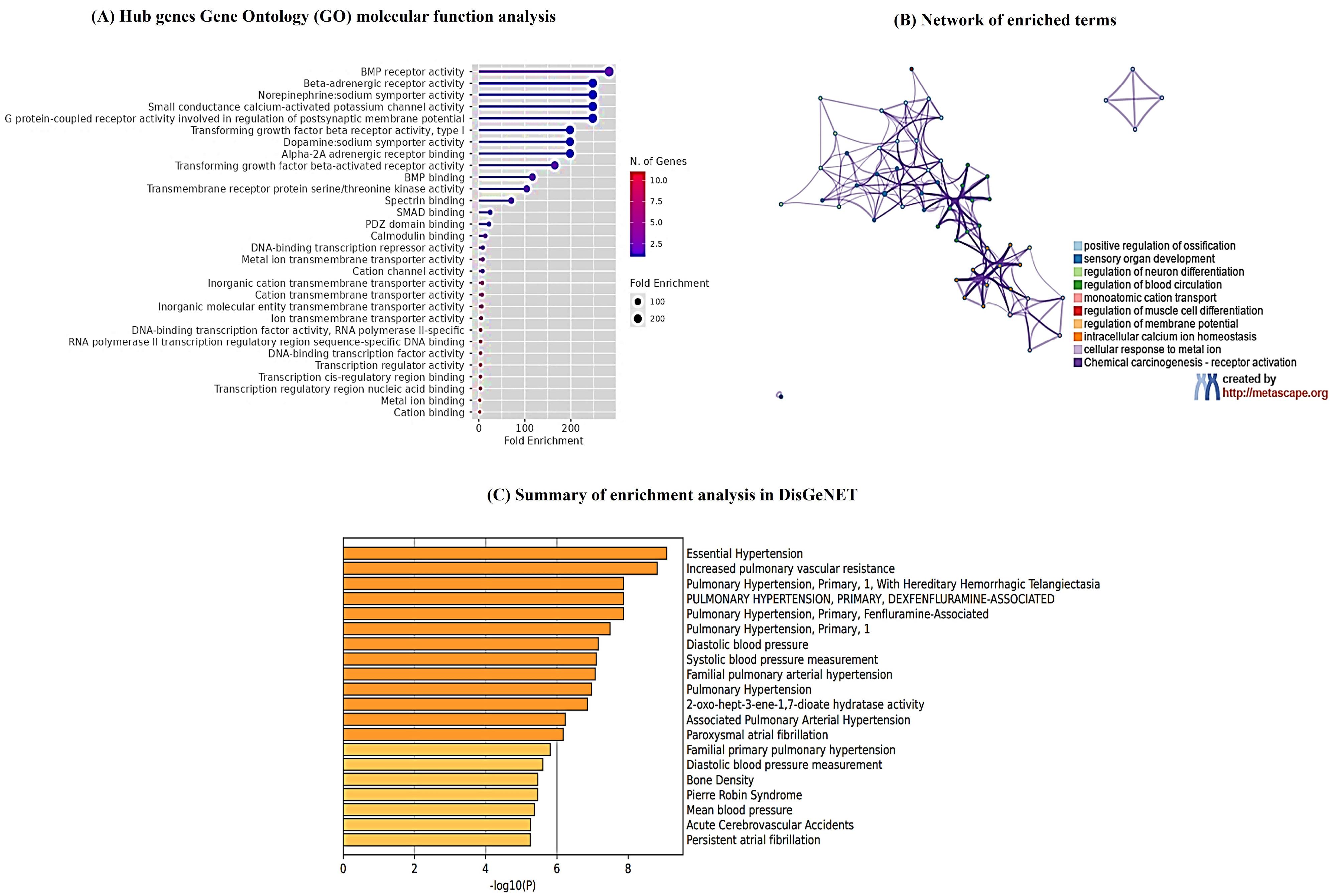

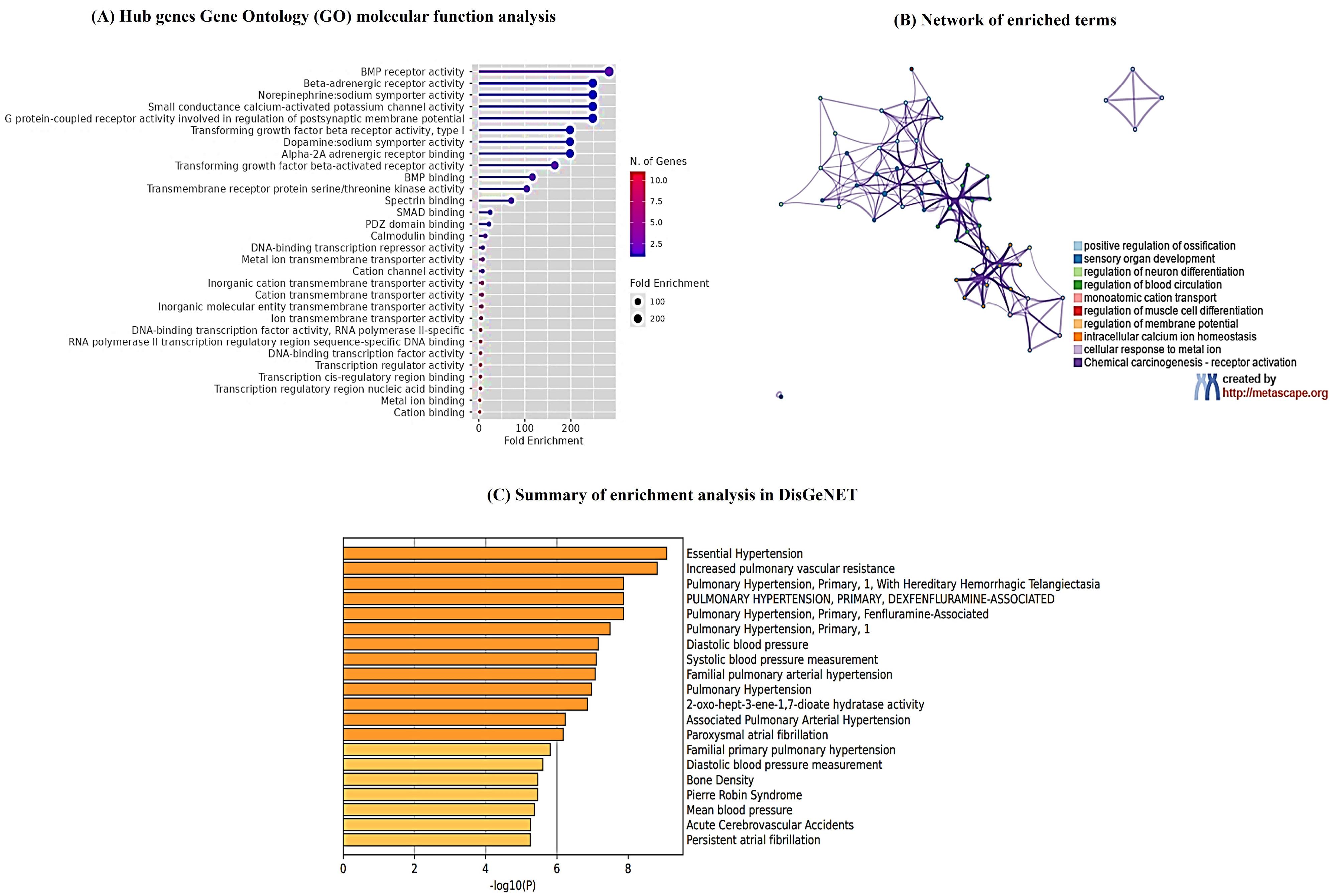

Gene enrichment analysis for genes associated with Sympathetic Cardio-Renal Axis

To investigate the specific biological function classification of DEGs and to validate our shortlisted genes, we executed the gene enrichment analysis using ShinyGO database. These genes showed enrichment in beta-adrenergic signaling, calcium signaling, non-epinephrine sodium symporter activity as well as GPCR signaling involved in post synaptic membrane potential as shown in Figure 6A. To further elucidate the relationship between DEGs, a network plot was constructed which displays enrichment in blood circulation, regulation of membrane potential and calcium ion homeostasis as shown in Figure 6B. Moreover, using DisGeNET algorithm, disease enrichment analysis demonstrated that hub genes were significantly associated with hypertension, vascular resistance, blood pressure, and atrial fibrillation as shown in Figure 6C.

Figure 6.

Gene enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes involved AFib pathogenesis (A) ShinyGO gene enrichment analysis revealed DEGs involvement in beta-adrenergic signaling, calcium signaling, non-epinephrine sodium symporter activity as well as GPCR signaling involved in post synaptic membrane potential. The x-axis represents the fold enrichment count, and the y-axis depicts enriched pathways. The color gradient from red to blue indicates the number of genes and concomitant fold enrichment variation in decreasing order. (B) Network of enriched terms by Metascape. Here each circle node represents a specific node, and size is proportional to the number of genes of that cluster, whereas color represents its cluster identity. Terms having similarity index > 0.3 are linked by an edge whose thickness represents the similarity score. (C) DisGeNET database enrichment analysis of different pathological conditions associated with genes. X axis represents -log10(P) value whereas y axis represents highly associated diseases with DEGs such as hypertension, vascular resistance, blood pressure, atrial fibrillation

.

Gene enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes involved AFib pathogenesis (A) ShinyGO gene enrichment analysis revealed DEGs involvement in beta-adrenergic signaling, calcium signaling, non-epinephrine sodium symporter activity as well as GPCR signaling involved in post synaptic membrane potential. The x-axis represents the fold enrichment count, and the y-axis depicts enriched pathways. The color gradient from red to blue indicates the number of genes and concomitant fold enrichment variation in decreasing order. (B) Network of enriched terms by Metascape. Here each circle node represents a specific node, and size is proportional to the number of genes of that cluster, whereas color represents its cluster identity. Terms having similarity index > 0.3 are linked by an edge whose thickness represents the similarity score. (C) DisGeNET database enrichment analysis of different pathological conditions associated with genes. X axis represents -log10(P) value whereas y axis represents highly associated diseases with DEGs such as hypertension, vascular resistance, blood pressure, atrial fibrillation

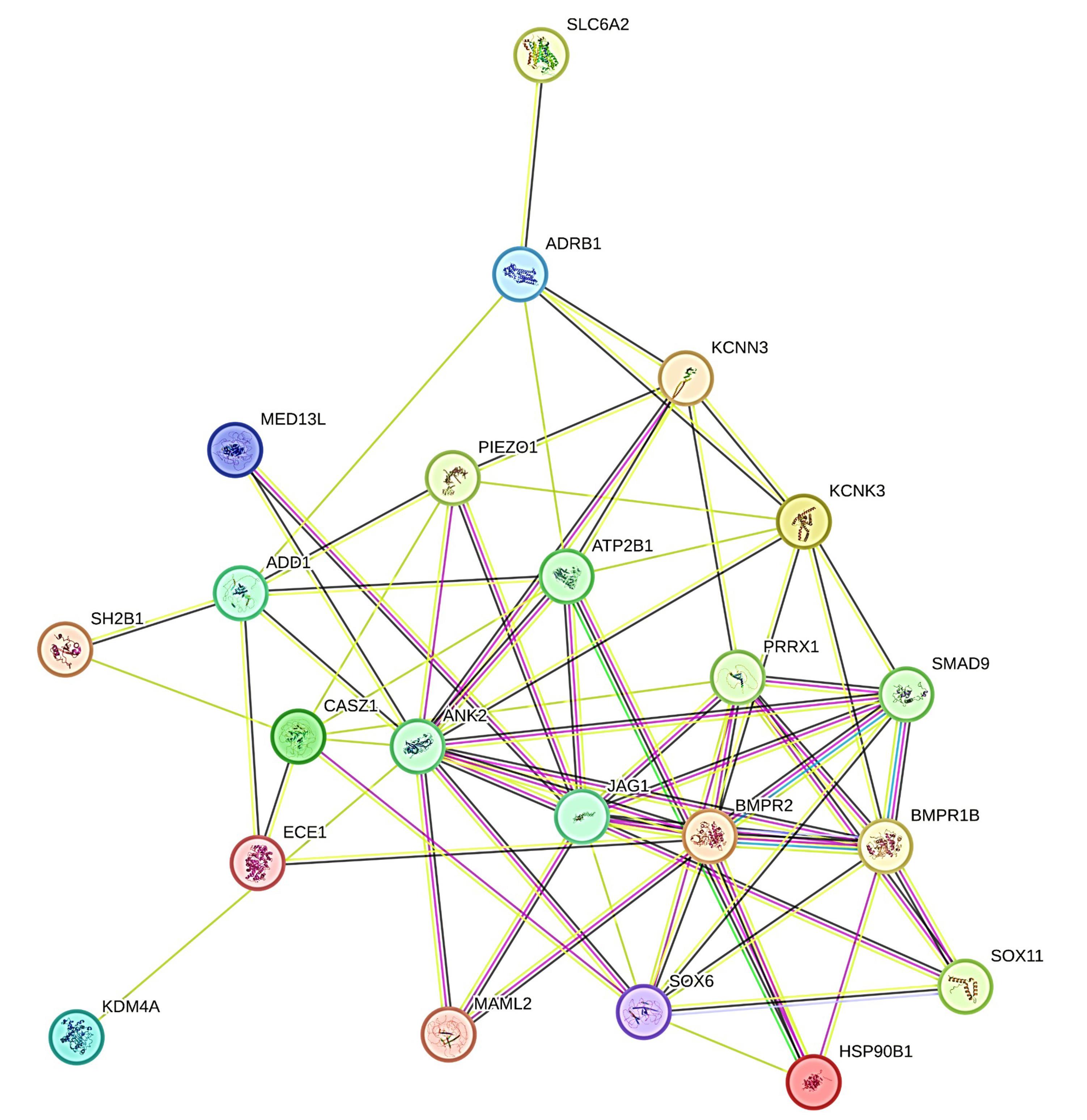

Construction of the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network and analysis of significant modules

The precise PPI network was constructed with a high-confidence interaction score (> 0.7) on the online tool STRING. 22 genes were found to be involved in the PPI pairs as shown in Figure 7. In this PPI network, there were 67 edges and 22 nodes having a PPI enrichment p-value of 1.11e-16. We selected 10 hub genes (i-e., ANK2, JAG1, BMPR2, BMPR1B, SOX6, ATP2B1, KCNK3, PRRX1, CASZ1, SMAD9) having the highest node degree interactions in the gene regulatory network as shown in (Table 3).

Figure 7.

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network; 22 genes were found to be predominantly involved in the PPI network, in which (i-e., ANK2, JAG1, BMPR2, BMPR1B, SOX6, ATP2B1, KCNK3, PRRX1, CASZ1, SMAD9) exhibit highest node degree interactions with p-value of 1.11e-16

.

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network; 22 genes were found to be predominantly involved in the PPI network, in which (i-e., ANK2, JAG1, BMPR2, BMPR1B, SOX6, ATP2B1, KCNK3, PRRX1, CASZ1, SMAD9) exhibit highest node degree interactions with p-value of 1.11e-16

Table 3.

Hub nodes, having the highest degree interactions in the gene regulatory network

|

Nodes

|

Degree Score

|

Nodes

|

Degree Score

|

| ANK2 |

14 |

PRRX1 |

8 |

| JAG1 |

11 |

SMAD9 |

7 |

| BMPR2 |

10 |

ADD1 |

6 |

| BMPR1B |

9 |

KCNK3 |

8 |

| SOX6 |

9 |

PRRX1 |

8 |

| ATP2B1 |

8 |

KCNN3 |

6 |

| KCNK3 |

8 |

PIEZO1 |

6 |

mRNA-miRNA network analysis

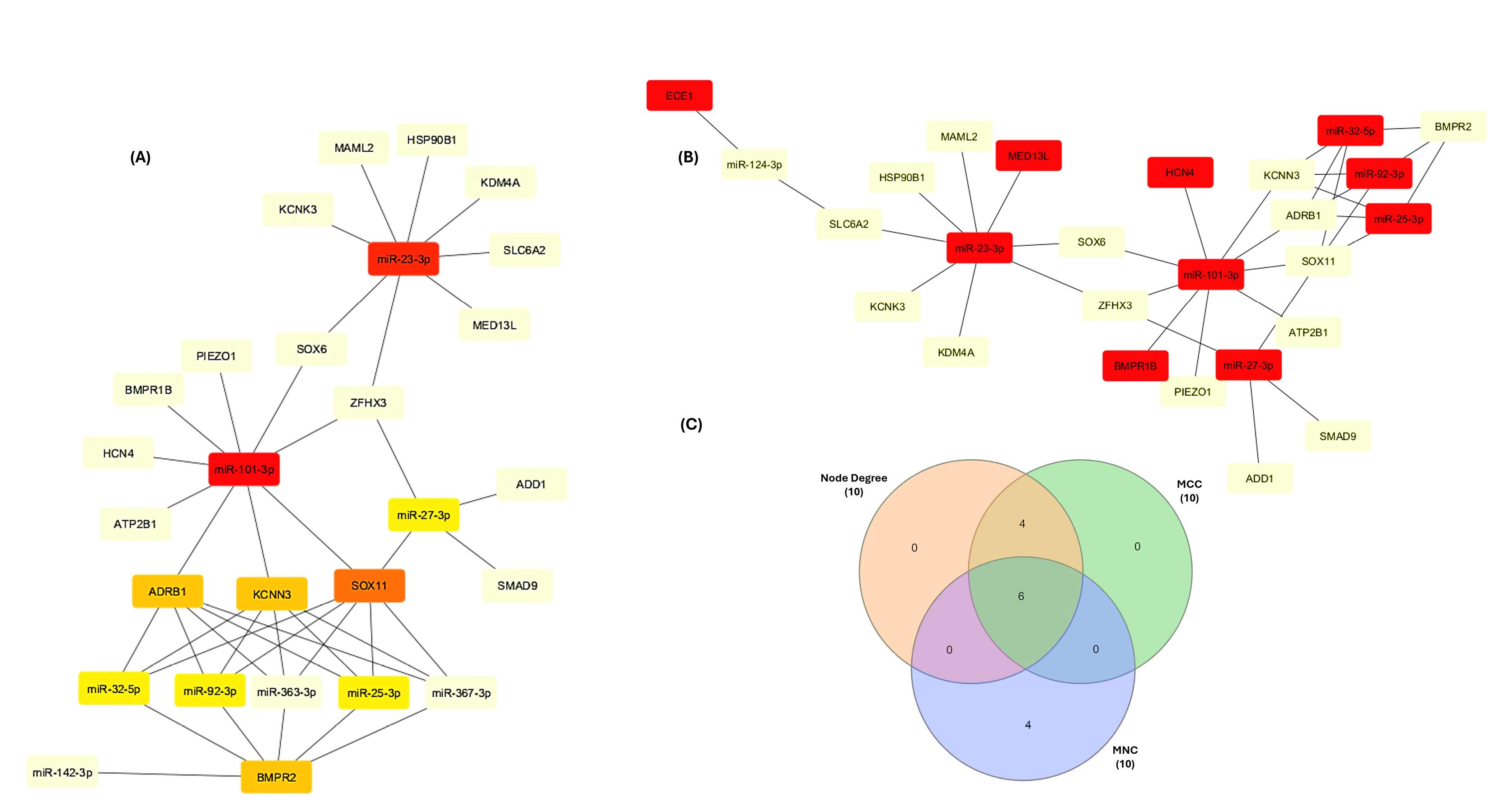

mRNA-miRNA network was constructed using Cytoscape (Figure 8). CytoHubba plugin identified crucial network hubs through three distinct methods: the maximal clique centrality (MCC) score, maximum neighborhood component (MNC) score, and highest degree score (Figure 9A & B). The intersection of top 10 modules having highest node degree, MNC, and MCC scores (Table 4) were considered as hub miRNAs, as shown in Venn diagram (Figure 9C). This robust pipeline for prioritizing potential disease modulators identified 6 hub miRNAs (miR-101-3p, miR-23-3p, miR-27-3p, miR-25-3p, miR-32-5p, miR-92-3p).

Figure 8.

miRNA-mRNA network using Cytoscape;Yellow color nodes represent miRNAs whereas blue color nodes represent their target genes

.

miRNA-mRNA network using Cytoscape;Yellow color nodes represent miRNAs whereas blue color nodes represent their target genes

Figure 9.

Identification of the hub genes and miRNAs (A) Top ranked genes and miRNAs using maximal clique centrality (MCC) algorithm and Node Degree rank. (B) Top ranked modules identified according to maximum neighborhood component (MNC) method. (C) Overlapped top ranked miRNAs and mRNAs from the MNC, MCC, and node degree methods. The red color nodes represent genes with highest sores, whereas the yellow color node represents low score

.

Identification of the hub genes and miRNAs (A) Top ranked genes and miRNAs using maximal clique centrality (MCC) algorithm and Node Degree rank. (B) Top ranked modules identified according to maximum neighborhood component (MNC) method. (C) Overlapped top ranked miRNAs and mRNAs from the MNC, MCC, and node degree methods. The red color nodes represent genes with highest sores, whereas the yellow color node represents low score

Table 4.

Top 10 genes and miRNAs scores ranked by MCC, MNC and Degree method

|

Rank

|

Name

|

Degree Score

|

Rank

|

Name

|

MCC Score

|

Rank

|

Name

|

Closeness Score

|

Rank

|

Name

|

MNC Score

|

| 1 |

miR-101-3p |

9 |

1 |

miR-101-3p |

9 |

1 |

miR-101-3p |

17.45 |

1 |

MED13L |

1 |

| 2 |

miR-23-3p |

8 |

2 |

miR-23-3p |

8 |

2 |

SOX11 |

16.316667 |

1 |

miR-92-3p |

1 |

| 3 |

SOX11 |

7 |

3 |

SOX11 |

7 |

3 |

miR-23-3p |

16.045238 |

1 |

miR-32-5p |

1 |

| 4 |

KCNN3 |

6 |

4 |

KCNN3 |

6 |

4 |

KCNN3 |

15.15 |

1 |

HCN4 |

1 |

| 4 |

ADRB1 |

6 |

4 |

ADRB1 |

6 |

4 |

ADRB1 |

15.15 |

1 |

miR-25-3p |

1 |

| 4 |

BMPR2 |

6 |

4 |

BMPR2 |

6 |

6 |

ZFHX3 |

15.033333 |

1 |

BMPR1B |

1 |

| 7 |

miR-27-3p |

4 |

7 |

miR-27-3p |

4 |

7 |

miR-27-3p |

14.116667 |

1 |

miR-27-3p |

1 |

| 7 |

miR-25-3p |

4 |

7 |

miR-25-3p |

4 |

8 |

SOX6 |

13.866667 |

1 |

ECE1 |

1 |

| 7 |

miR-32-5p |

4 |

7 |

miR-32-5p |

4 |

9 |

BMPR2 |

13.527381 |

1 |

miR-101-3p |

1 |

| 7 |

miR-92-3p |

4 |

7 |

miR-92-3p |

4 |

10 |

miR-25-3p |

13.378571 |

1 |

miR-23-3p |

1 |

Screening of differentially expressed miRNAs (DEMs) in clinical AFib patient’s datasets

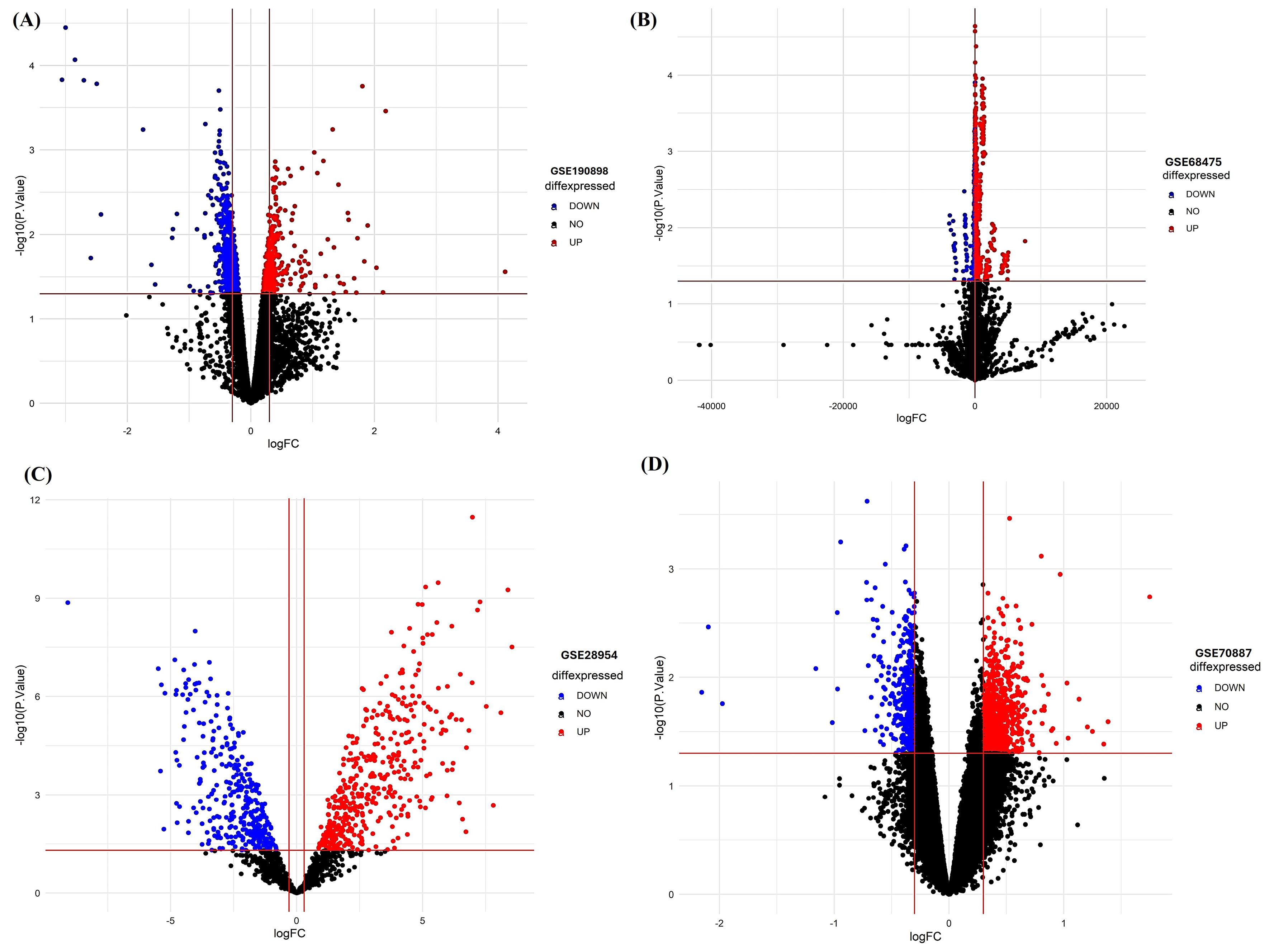

We then sought to determine the reproducibility of the initial profiling of hub miRNA signatures in multiple independent datasets (Table 5). DEMs passing the criteria of P< 0.05 and log2|fold change| > 1 were considered as the potential candidates, as given in (Table S5-S8). Differentially expressed hub miRNAs are shown in Volcano plots in Figure 10 A-D.

Table 5.

Differentially expressed hub miRNAs

|

miRNAs

|

log FC

|

p

-value

|

Datasets Accession IDs

|

|

hsa-miR-101

|

8.975409 |

0.04108 |

GSE68475 |

| 1.498829 |

0.0384 |

GSE190898 |

|

hsa-miR-23a

|

6.814861 |

0.042828 |

GSE68475 |

|

hsa-miR-25

|

-9.20899 |

0.005195 |

GSE68475 |

| 0.241439 |

0.03505 |

GSE28954 |

| -0.13165 |

0.043473 |

GSE70887 |

|

hsa-miR-32

|

9.508575 |

0.006066 |

GSE68475 |

|

hsa-miR-92b

|

11.60204 |

0.004529 |

GSE68475 |

|

hsa-miR-27

|

15.41865 |

0.00703 |

GSE68475 |

Figure 10.

Volcano plots of differentially expressed miRNAs from multiple datasets (A) GSE190898 (B) GSE68475, (C) GSE28954 (D) GSE70887

.

Volcano plots of differentially expressed miRNAs from multiple datasets (A) GSE190898 (B) GSE68475, (C) GSE28954 (D) GSE70887

Discussion

The vicious cycle of three systemic biological systems, i.e., sympathetic, renovascular, and cardiovascular systems, form a most crucial and responsive network throughout the body that is responsible for AFib. 34,35 Thus, it is of paramount importance to scrutinize the molecular mechanisms that exacerbate disease severity in AFib patients. For this, an attempt has been made to find out the hub miRNAs through integrated bioinformatics approaches.

The genes from GWAS enlisted in NCBI GTR, OMIM, and Gene Card and differentially expressed genes of GSE41177 and GSE79768, only overlapped genes were selected for further analysis. For in-depth analysis of gene sets, ShinyGO enrichment analysis was performed separately on all three genes sets. Taken together, downstream analysis of hub genes and associated miRNAs with AFib and symaptho-cardiorenal axis render valuable information regarding crucial aspects of affected biological processes, dysregulated cellular pathways, associated diseases, and diagnostic biomarkers. Many of the genes associated with AFib were found to underpin molecular responses such as membrane depolarization, sinoatrial action potential generation, and muscles contraction, regulation of ions transmission and regulation of heart rate. Whereas analysis of genes associated with SNS activity exhibited enriched terms in sympathetic nervous system development, autonomic nervous system activity, circulatory system processes, cell-cell signaling, and homeostatic signaling. Enrichment analysis of RVH associated genes showed enrichment in processes including blood vessels remodeling, pulmonary and aortic valves development and pharyngeal system development. Next, we performed computational screening of highly specific and accurate miRNAs interacting with shortlisted genes by using TargetScan database. MiRNAs having 8-mer binding seed region in the 3ÚTR of genes were selected. We shortlisted miRNAs (miR-23-3p, miR-101-3p, miR-27-3p, miR-25-3p, miR-32-5p, miR-92-3p, miR-363-3p, miR-367-3p, miR-124-3p, miR-506-3p, miR-142-3p) common in all pathologies (AFib, SNS hyperactivity and RVH).

Target genes were then subjected to DisGeNET database for enrichment analysis with respect to diseases. Results revealed enrichment in hypertension, vascular resistance, blood pressure, atrial fibrillation which further endorsed our findings. The precise PPI network was constructed on STRING. 10 hub genes (i-e., ANK2, JAG1, BMPR2, BMPR1B, SOX6, ATP2B1, KCNK3, PRRX1, CASZ1, SMAD9) were found to have the highest node degree interactions in the gene regulatory network. Furthermore, using CytoHubba plug-in, we identified top level modules using 3 different methods i.e., the maximal clique centrality (MCC), maximum neighborhood component (MNC), and degree method. The intersection of top 10 modules having highest node degree, MNC, and MCC scores were considered as hub miRNAs (i.e., miR-101-3p, miR-23-3p, miR-27-3p, miR-25-3p, miR-32-5p, miR-92-3p). We integrated miRNA expression profiles of AF samples from 4 GEO datasets and analyzed the data using R software and bioinformatics tools. The expression of hub miRNAs was also found to be significantly dysregulated in patients as compared to healthy individuals.

After comprehensive profiling of miRNAs, miR-101-3p was found to be key miRNA in co-expression network having highest MCC score. MiR-101-3p has protective effects on atrial fibrillation as it increases the atrial effective refractory period, thus reducing the AFib incidence. 36 Another study also reported that miR-101 could inhibit fibrosis by targeting proto-oncogene (c-Fos), a potential biomarker for neuronal activity and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β) coding gene. MiRNA target prediction through databases revealed ZFHX3, HCN4, KCNN3, ADRB1, SOX11, PIEZO1, ATP2B1, BMPR1B and SOX6 contain 8-mer binding sites for miR-101-3p. However, no in vivo experimentation regarding aforementioned genes with miR-101-3p has been reported yet.

Apart from electrical remodeling due to ionic imbalance, structural remodeling is another crucial process in AFib pathophysiology and is marked by atrial fibrosis. 37 Our findings also emphasize miR-27-3p as the most important regulator of AFib pathogenesis. In silico analysis for miRNA prediction using TargetScan database showed that ZFHX3, SOX11, ADD1 and SMAD9 are potential target genes of miR‐27‐3p. Previous study also reported that miR‐27‐3p promote atrial fibrosis by targeting SMAD signaling pathway thus leading to atrial fibrosis.38 The pathophysiology of AFib is manifested by upregulation of fibrosis related genes and down regulation of ion channels encoding genes that cause disturbance in cardiac electrical activity. miR-27-3p also reportedly involved in electrical remodeling through HOXa10, resulting in a decreased expression of voltage-gated sodium (Nav1.5), potassium (Kv4.2), and calcium (Cav1.2) channels encoded by SCN5A, KCND2 and CACNA1C gene respectively. 39 Concomitantly another study reported that miR-27b increases vulnerability to cardiac arrhythmia leading to conduction disturbance by targeting atrial gap junction coding gene connexin-40 (CX40).40

Predictive analysis by TargetScan database revealed the presence of binding sites of miR-23-3p in 3’ UTR region of genes i.e., ZFHX3, SLC6A2, HSP90B1, KDM4A, KCNK3, MAML2, SOX6 and MED13L. MiR-23-3p is involved in ferroptosis in atrial fibrillation patients by targeting SLC7A11.41 Another study reported that miR-23-3p perpetuate AFib progression by regulating TGF-β1.42 Similar pattern observed with miR-25-3p that promotes atrial fibrosis by suppressing Dickkopf 3 (Dkk3), an enhancer of SMAD7 expression, that activate SMAD3 and fibrosis-related genes expression.43

Another key finding of our integrated bioinformatic analysis underlies the identification of miR-32-5p and miR-92-5p that has not been reported in prior studies related to AFib. Furthermore, both miRNAs have been computationally predicted to have evolutionary conservation and 8-mer binding sites for calcium-activated potassium channel gene (KCNN3), SRY-box transcription factor (SOX11), Adrenoceptor Beta 1 (ADRB1), and Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II (BMPR2). MiR-32-5p and miR-92-5p have pleiotropic effects and can target both structural and electrical remodeling causing genes simultaneously, thus highlighting their potential as promising therapeutic targets for the treatment of AFib patients.

The current study has a few limitations. The hub genes were identified by bioinformatics analysis, necessitating experimental research for validation of the findings. Despite these constraints, this study possesses promise as it offers novel insights into the pathophysiology and therapeutic targets of AFib by employing an integrated multi-step computational workflow to extract high-level evidence from various datasets, hence increasing the utility of available bioinformatics resources.

Conclusion

Our study integrated microarray-based miRNA and mRNA expression profiles from datasets comprising multiple cohorts and series of bioinformatics analyses. Concomitantly, disease targets related to sympathetic cardio-renal axis were screened from NCBI GTR and OMIM, which provides rationale in exploring the molecular basis of evading genes and miRNAs. Through extensive bioinformatics analytic workflow, we identified 6 hub miRNAs, 4 previously reported (miR-101-3p, miR-23-3p, miR-27-3p, miR-25-3p) and 2 novel (miR-32-5p, miR-92-3p) miRNAs for AFib that might act as putative biomarkers. The findings of our study are essential for the establishment of precision medicine initiatives, as they contribute to the comprehension of the genetic and molecular basis of AFib. Subsequent research is necessary to substantiate the molecular mechanisms that underline these findings.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any research involving animals or humans as subjects of research.

Supplementary Files

Supplementary file Contains Table S1-S8.

(xlsx)

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the university research fund (URF) of Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Higher Education Commission (HEC) Pakistan, and Pakistan Science Foundation (PSF) to support the current study.

References

- Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019; 139(10):e56-528. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000659 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kornej J, Börschel CS, Benjamin EJ, Schnabel RB. Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in the 21st century: novel methods and new insights. Circ Res 2020; 127(1):4-20. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.120.316340 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wijesurendra RS, Casadei B. Mechanisms of atrial fibrillation. Heart 2019; 105(24):1860-7. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314267 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Heijman J, Linz D, Schotten U. Dynamics of atrial fibrillation mechanisms and comorbidities. Annu Rev Physiol 2021; 83:83-106. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-031720-085307 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Carnagarin R, Kiuchi MG, Ho JK, Matthews VB, Schlaich MP. Sympathetic nervous system activation and its modulation: role in atrial fibrillation. Front Neurosci 2018; 12:1058. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.01058 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Carnagarin R, Matthews V, Zaldivia MTK, Peter K, Schlaich MP. The bidirectional interaction between the sympathetic nervous system and immune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Br J Pharmacol 2019; 176(12):1839-52. doi: 10.1111/bph.14481 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sidhu B, Mavilakandy A, Hull KL, Koev I, Vali Z, Burton JO. Atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease: aetiology and management. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2024; 25(4):143. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm2504143 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sata Y, Head GA, Denton K, May CN, Schlaich MP. Role of the sympathetic nervous system and its modulation in renal hypertension. Front Med (Lausanne) 2018; 5:82. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00082 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tapoi L, Ureche C, Sascau R, Badarau S, Covic A. Atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease conundrum: an update. J Nephrol 2019; 32(6):909-17. doi: 10.1007/s40620-019-00630-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kiuchi MG. Atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease: a bad combination. Kidney Res Clin Pract 2018; 37(2):103-5. doi: 10.23876/j.krcp.2018.37.2.103 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pugliese NR, Masi S, Taddei S. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system: a crossroad from arterial hypertension to heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2020; 25(1):31-42. doi: 10.1007/s10741-019-09855-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Donniacuo M, De Angelis A, Telesca M, Bellocchio G, Riemma MA, Paolisso P. Atrial fibrillation: epigenetic aspects and role of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. Pharmacol Res 2023; 188:106591. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106591 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Han P, Zhao X, Li X, Geng J, Ni S, Li Q. Pathophysiology, molecular mechanisms, and genetics of atrial fibrillation. Hum Cell 2024; 38(1):14. doi: 10.1007/s13577-024-01145-z [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hussain K, Ishtiaq A, Mushtaq I, Murtaza I. Profiling of targeted miRNAs (8-nt) for the genes involved in type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiac hypertrophy. Mol Biol (Mosk) 2023; 57(2):338-45. doi: 10.1134/s0026893323020085 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Thahiem S, Iftekhar MF, Faheem M, Ishtiaq A, Jan MI, Khan RA. Elucidation of potential miRNAs as prognostic biomarkers for coronary artery disease. Hum Gene (Amst) 2025; 43:201385. doi: 10.1016/j.humgen.2025.201385 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Huang X, Wang X, Gao Y, Liu L, Li Z. Identification of potential crucial genes in atrial fibrillation: a bioinformatic analysis. BMC Med Genomics 2020; 13(1):104. doi: 10.1186/s12920-020-00754-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Qu Q, Sun JY, Zhang ZY, Su Y, Li SS, Li F. Hub microRNAs and genes in the development of atrial fibrillation identified by weighted gene co-expression network analysis. BMC Med Genomics 2021; 14(1):271. doi: 10.1186/s12920-021-01124-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yan T, Zhu S, Zhu M, Wang C, Guo C. Integrative identification of hub genes associated with immune cells in atrial fibrillation using weighted gene correlation network analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2020; 7:631775. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.631775 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Huang K, Fan X, Jiang Y, Jin S, Huang J, Pang L. Integrative identification of hub genes in development of atrial fibrillation related stroke. PLoS One 2023; 18(3):e0283617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0283617 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Triposkiadis F, Briasoulis A, Kitai T, Magouliotis D, Athanasiou T, Skoularigis J. The sympathetic nervous system in heart failure revisited. Heart Fail Rev 2024; 29(2):355-65. doi: 10.1007/s10741-023-10345-y [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb LA, Mahfoud F, Stavrakis S, Jespersen T, Linz D. Autonomic nervous system: a therapeutic target for cardiac end-organ damage in hypertension. Hypertension 2024; 81(10):2027-37. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.123.19460 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Akrawinthawong K, Yamada T. Emerging role of renal sympathetic denervation as an adjunct therapy to atrial fibrillation ablation. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2024; 25(4):122. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm2504122 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein WS, Maglott DR, Lee JM, Kattman BL, Malheiro AJ, Ovetsky M. The NIH genetic testing registry: a new, centralized database of genetic tests to enable access to comprehensive information and improve transparency. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 41(D):D925-35. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1173 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Clough E, Barrett T. The gene expression omnibus database. Methods Mol Biol 2016; 1418:93-110. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3578-9_5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Heberle H, Meirelles GV, da Silva FR, Telles GP, Minghim R. InteractiVenn: a web-based tool for the analysis of sets through Venn diagrams. BMC Bioinformatics 2015; 16(1):169. doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0611-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ge SX, Jung D, Yao R. ShinyGO: a graphical gene-set enrichment tool for animals and plants. Bioinformatics 2020; 36(8):2628-9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz931 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones S, Grocock RJ, van Dongen S, Bateman A, Enright AJ. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res 2006; 34(D):D140-4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj112 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dweep H, Sticht C, Pandey P, Gretz N. miRWalk--database: prediction of possible miRNA binding sites by “walking” the genes of three genomes. J Biomed Inform 2011; 44(5):839-47. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.05.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife 2015; 4:e05005. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Piñero J, Bravo À, Queralt-Rosinach N, Gutiérrez-Sacristán A, Deu-Pons J, Centeno E. DisGeNET: a comprehensive platform integrating information on human disease-associated genes and variants. Nucleic Acids Res 2017; 45(D1):D833-9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw943 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res 2019; 47(D1):D607-13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chin CH, Chen SH, Wu HH, Ho CW, Ko MT, Lin CY. cytoHubba: identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol 2014; 8 Suppl 4:S11. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-8-s4-s11 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kim SM, Jeong Y, Kim YL, Kang M, Kang E, Ryu H. Association of chronic kidney disease with atrial fibrillation in the general adult population: a nationwide population-based study. J Am Heart Assoc 2023; 12(8):e028496. doi: 10.1161/jaha.122.028496 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mohanta SK, Sun T, Lu S, Wang Z, Zhang X, Yin C. The impact of the nervous system on arteries and the heart: the neuroimmune cardiovascular circuit hypothesis. Cells 2023; 12(20):2485. doi: 10.3390/cells12202485 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Qiao J, Yao K, Yuan Y, Yang X, Zhou L, Long Y, et al. Disentangling shared genetic etiologies for kidney function and cardiovascular diseases. medRxiv [Preprint]. July 27, 2024. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.07.26.24310191v1.

- Zhu J, Zhu N, Xu J. miR-101a-3p overexpression prevents acetylcholine-CaCl2-induced atrial fibrillation in rats via reduction of atrial tissue fibrosis, involving inhibition of EZH2. Mol Med Rep 2021; 24(4):740. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2021.12380 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nattel S, Heijman J, Zhou L, Dobrev D. Molecular basis of atrial fibrillation pathophysiology and therapy: a translational perspective. Circ Res 2020; 127(1):51-72. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.120.316363 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Xiao Z, Guo H, Fang X, Liang J, Zhu J. Novel role of the clustered miR-23b-3p and miR-27b-3p in enhanced expression of fibrosis-associated genes by targeting TGFBR3 in atrial fibroblasts. J Cell Mol Med 2019; 23(5):3246-56. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14211 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Xi S, Wang H, Chen J, Gan T, Zhao L. LncRNA GAS5 attenuates cardiac electrical remodeling induced by rapid pacing via the miR-27a-3p/HOXa10 pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2023; 24(15):12093. doi: 10.3390/ijms241512093 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Sasano T, Sugiyama K, Kurokawa J, Tamura N, Soejima Y. High-fat diet increases vulnerability to atrial arrhythmia by conduction disturbance via miR-27b. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2016; 90:38-46. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.11.034 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Yang M, Yao Y, He S, Wang Y, Cao Z. Cardiac fibroblasts promote ferroptosis in atrial fibrillation by secreting Exo-miR-23a-3p targeting SLC7A11. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022; 2022:3961495. doi: 10.1155/2022/3961495 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wen JL, Ruan ZB, Wang F, Hu Y. Progress of circRNA/lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA axis in atrial fibrillation. PeerJ 2023; 11:e16604. doi: 10.7717/peerj.16604 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zeng N, Wen YH, Pan R, Yang J, Yan YM, Zhao AZ. Dickkopf 3: a novel target gene of miR-25-3p in promoting fibrosis-related gene expression in myocardial fibrosis. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2021; 14(6):1051-62. doi: 10.1007/s12265-021-10116-w [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]